Project Summary

words & photography by: Martha Molfetas

November 2017

Over the last year, we've interviewed people directly impacted by Hurricane or 'Superstorm' Sandy. Over these last twelve months, we've met with and heard from seven people, and with each story we've gained new insight into just how devastating Sandy was for so many. Our team went out and photographed many of the areas affected by Sandy, all included here. While Sandy struck the NYC-area on October 29th, 2012 - somehow many parts of the city remain in disrepair, or are still being rebuilt - five years later. New York and New Jersey were not alone, Sandy wove its way from the Caribbean to Canada, killing 147 in it's path - including 43 people in the NYC area alone.

This project aims to shine a light on the devastation Sandy caused and what has been done since to build coastal and climate resiliency and respond to the aftermath here in NYC. The photographs included here were taken on location from June to November 2017 - in order to best show how the city is doing, five years later. We went to Coney Island, and as far as Seaford, NY; and countless spots in-between. From Staten Island to Hoboken, Sandy left her mark on the NYC-area and beyond, forcing us all to reconsider just how prepared we are for hurricanes and storms, and what we can do to turn the tide on climate change.

While climate change cannot cause any particular storm or hurricane, climate impacts like sea level rise and ocean warming fuel storms, increase their strength, and create more intense storm surges. Real people are impacted by climate change and climate injustice. Cities like NYC will become increasingly vulnerable to sea level rise and intense storm surges. Among cities in the United States, NYC ranked first place for the most at risk from coastal flooding today, and with future anticipated sea level rise by 2050. All in all, Sandy can prove to be a turning point for the NYC-area; we can learn to respond to storms like this better, and we can learn how to build resiliency into future planning. These sorts of policies can save lives and prevent future devastation. Unfortunately, storms like Sandy will be a part of all our futures, rather than an outlier from our past.

Research brief

For more insight on the damage caused by Hurricane Sandy and what the city is doing, five years later, you can download our short Research Brief below.

people

Hover your mouse over the image to see interview quotes and descriptions.

"There were a lot of areas that I guess didn't realize that we were going to have such a strong impact from it. It was night time , [I was] watching all the areas on the news that were being hit and all of a sudden a big blast comes through. It was almost like a giant rush - I don't even know how to describe it."

"The Sound was so horrible. It was so fast and immediate. The rush of the water coming from up the hill down slashed our a whole community, busted through a metal door in our basement - a metal door pushed in. And all of the water was forced from the manholes, they were pushed up as the water rushed down and filled up the street. I would say it wasn't even waist [deep] at the time it was shoulder height."

"You know, everybody in the building that I was in - it was a small five story brownstone, it's a co-op, - and we all ran downstairs to see what was going on obviously. There was no lights we look downstairs at the steps to the basement. The water is coming all the way up to the first floor. We looked down in the street where you had like eight steps like a brownstone in the front - it was coming up all the way to the top. We couldn't even leave the building. The rain the water it just looked like there was no end that it was going to stop."

"I was on the third floor. The whole basement was coming up to the first floor. It was so frightening that we just couldn't imagine. We just couldn't deal with or comprehend what was going on, it was so shocking and devastating. That's when I notified my family and my people and learned what's going on in their area. My mother happened to be living in Long Beach so they were in the same situation I was in. So looking for an alternative place to go, it would not have helped for me to have left my place to go to theirs in Queens - from New Jersey to Queens."

"At that time we had no choice but to wait it out until the sun comes up to see what it looks like at that point, like I said, the water was still rising. It was coming up higher and higher and all we [could] do [was] get flashlights and look to see how far the water was going to rise. I went and salvaged my transistor radios and there were people in the building that did not have one - I was lucky, fortunate to have two. So I lent them one. We all kind of took care of each other, at that time, but there was nothing we could do, period."

"We couldn't get out of the building. We were stuck, trapped in the building. The water was contaminated on top of that. So I wasn't even trying to get out there with shoulder high water with the sewer right there that came up from above that. It was terrifying. It was something I could not believe."

"They did not bring anybody in. People were pulling out their row boats and paddling all over the place, just to see the devastation, what's going on. There were no stores open. Hoboken is a very small town. Everything was devastated, just shut down - the whole town. Nothing was left... it took one week [for emergency response to arrive]."

"Just like I said, you see what's happening in Puerto Rico and in North Carolina with the surge. The surge is something else. It's not the rain, it's not the wind, it's that surge that was so high it came over Sinatra Boulevard Park right over that and then went uphill and smashed downhill. That's when it pushed in the metal door to the basement, a thick metal door was broken in. [I] couldn't believe that, the force of that fence, the metal fence turned over. I saw refrigerators floating in the street - stuff like that - and you're wondering where did this refrigerator come from? There was a rodent problem, but after that there was no more because everything flooded, so silver lining... at least it was good for something."

"I actually grew up on the water and interestingly never had anything close to a Sandy experience, which says a lot, considering that was from [and] I lived there from 1982 until 2001, my parents lived there anyway and they never got a drop of water, even in the backyard.

In this day and age given what's going on with climate change, and the reality that areas that have never know storms like this are being hit regularly. I feel like there's got to be like if I can put my energy towards this issue, where would I go? What would I say? What would I do? All I just do is tell everyone that I know - get flood insurance."

"Hurricane Irene had happened almost exactly a year before, it was like August of 2011 and it was predicted to be bad and we were technically in [the] evacuation zone. Clearly [we] didn't make the right choice - but we were sort of predisposed to think that there was a bit of an alarmist media created frenzy, which I think is a problem. And I think because of the severity of storms now, it's starting to become less of a problem, but I do look back on that and feel very strongly that it was hard to sort out what was a real threat and what wasn't. In any case, we were pretty sure we were going to be in for something, like I remember the weekend before Sandy, we were finally told over the weekend that you should evacuate. I think it was recommended but not mandatory. And because I was pregnant I didn't really want to sleep on someone else's floor, and the reality is, we just didn't have a lot of places to go because so many people - I mean, everybody we knew was being effected. My in-laws had major damage. My dad lives in Amityville by the water. My sister lives in Delaware."

"We really just felt like, there wasn't anywhere to go and we were going to be fine. Then the day of the storm... the only thing I recall seeing is this constant focus on the crane that was in the middle of the city. That was banging into a building, and that was the only coverage. I actually had a doctor's appointment and went to it and then got home. And I guess around 4 pm.. we started hearing if you're in an evacuation zone, and you didn't evacuate, you're on your own. First Responders won't be able to get to you. [Around] 7pm we still had power, we were sitting in the house, everything seemed fine and then we noticed that some of our neighbors were outside and my husband said "oh I'm going to go check it out" and all sudden the entire block went dark, because as it turns out, the town shut the power grid off to avoid fires. So he came back, and he's like "there's a lot of water in the street". And I thought wow that's weird, and by the time we looked back out it was like a river coming. So we literally grabbed 2 black contractor bags shoved as much as we could... We just grabbed what we thought we would need. Actually our next door neighbors had called and said "we can see the water and we're upstairs and we're really concerned you guys have to come over". So we did, and by the time we got outside, the water was up to my waist. I'm 5'3'', so I would say it was a couple of feet. We got upstairs in their house, and it just came pouring from both directions and at different points in the house the watermarks we're different. In this part of the house, it went up to that landing - about 4 feet"

"Considering it was one floor, every wall was touched and what actually ended up being equally devastating was that the insulation pulled the water up, so we had 8 feet of mold around the perimeter of the house, so it was pretty bad. We stayed there that night. We came back in the morning and saw the damage. We tried to see if the cars would start. One of them did, which was a weird miracle, because it didn't last long and we shouldn't have driven it. Geico said "you really should not have driven that car". We were lucky it didn't catch on fire, but we didn't have a lot of options... We got to my dad's, and the issue after that was power. Because even people who had been spared the water, were anyone we knew within a reasonable distance had no power and it was cold and I'm pregnant so we kind of spent that day trying to figure out where we were going to live. The first few weeks we bounced around with whoever had room and power... So you know, the hardest parts were obviously for the kids, just the complete chaos of their routine. The kids were 6 and 4."

"We were lucky that we had a contractor that was available and they said the first thing that we needed to do was just rip everything out, like get everything out so mold stops growing. They ripped up the floors and the walls, the insulation... But the other risk at that point was that the pipes would freeze because there is no heat and it was winter. So there was a combination of like a lot of things: cool air, hot air, a lot of things you just didn't think of... We were very fortunate with our insurance. Geico was great. FEMA was great. They all had very well organized local pop up disaster centers. There was one in our Park [and] one at a local University. Our mortgage company had a little pop up, which they had nothing to offer us. Yeah they were like "yeah you still have to pay your mortgage". I was like we aren't there and it's not even a house. So paying for a mortgage and insurance and taxes on a house that you don't live in and you're renting somewhere else. That was stressful, so we had to borrow a lot of money. It took us a long time to pay back but we were very fortunate that we had people that could lend us money and we kind of just got through it. You just kind of have to look for resources that you have."

"Everything was fine on the day that Sandy actually hit. Throughout the day, conditions were okay, you know there was some minor flooding on the beach, but then at around high tide in the evening, so let’s say I think it was 5:30 - 6:00 o’clock, the water started coming up in the street and you know I went outside and I looked and I went back in and I told my husband “It’s actually - there’s water in the street” and he’s like “Ah, it’s not a big deal”. And then we went back out and it was up on the sidewalk and I said, “You know we should probably go tell Jackie and Mike [who were our tenants downstairs] to come upstairs” and so we went and knocked on the door and they said yeah you’re right cuz they looked and saw it was on the sidewalk and so they went upstairs."

"Their apartment was six inches below grade so when you stepped in you walked down two steps. And so at that point we were like “we should get the cats out.” So we started collecting the cats and we formed a little brigade and we were grabbing cats who were going like this [gesture], you know, and walking them through the water up into our apartment. And by the time we got the last cat I wading in water up to my chest and the electricity pole on our street started sparking and all the lights went out and I was like, “Okay, I’m wading in water up to my chest carrying a cat that is scratching me and I’m going to be electrocuted.” And we got into the house and you know the power was out and we just sort of all sat - oh and meanwhile our cars were going through their death knells like you know the minute the water hit the sort of panels that start the car alarms went off - so they were you know the car alarms all around the street the car alarms went off but they were sort of being drowned by the water so there was this horrible sort of deadening noise like you know car alarms dying “wah, wah, wah” you know and in the end the waters was up to the ceiling in both cars. So we lost both our cars. So we got into the house and we all just sat there shellshocked, didn’t really say much. But In the back of my mind was, I mean we were fine, we were dry upstairs but when we left the apartment the last time the refrigerator was floating, you know the water was about five and half feet deep in their apartment."

"I couldn’t really think about myself, I was thinking more about them, and we really didn’t talk much because that was the elephant in the room basically...We slept maybe three hours and then by I would say by 3 or 4am the water had receded and they were able to go downstairs and when I woke up they were already you know Jackie was sobbing, you know like all of her pictures, all of her papers, everything from her life, all of her mementos were gone."

"That’s what we woke up to. And it wasn’t just us. What we realized - you know, it’s sort of like when you’re in a nightmare dream and you wake up and you’re, you think you’re okay but then you’re in another dream you know, where your dream has layers? We were walking around the neighborhood and when I realized how bad it was I was shocked. And you know we realized then that we couldn’t get out either, we had no cars, and there were sand banks everywhere adrift - the streets were full of sand dunes that had sort of been deposited by the water. Cuz the water came up both sides of the island."

"The trains weren’t running, your car was gone. No one’s cars survived, whether it was in a garage or not. So there was really no way out. And the National Guard came in right away. They were handing out those packets of food, you know the [unintelligible] water. People were living like that. So right away I could feel how we were different, you know the fact that we got rescued and we were taken to Tom’s parents’ house and our tenants like you know went somewhere else, I forget where they went, someone they knew had an empty apartment that was on a high floor so they went there. But you know, everybody was, everyone was basically shut out of habitable livings but they lived there anyway. And it was freezing, I don’t know if you remember, the week after there was a snow storm."

"We had to basically gut out tenants’ apartment, throw out all of their life’s possessions, put them in a pile that came to 7-feet tall by 12-feet wide and 3-feet deep. All the appliances, everything, we had to gut that apartment down to the studs and there was nothing left. And we rebuilt the entire thing right away. Like Tom went to the bank the day after the hurricane happened and he took out our entire line of credit and he deposited it in our checking account cuz he figured we might need it cuz you know banks have will shut down lines of credit, they realize, 'oh that’s Long Beach, we’re not gonna'. And so we had access to cash and we rebuilt the apartment and our tenants actually moved back in two days before Christmas. Which I’m still, to this day, I’m blown away by the fact."

"Because you know, one thing I want to say, before Sandy our apartment downstairs was a legal apartment but we were sort of grandfathered in because the house was built in 1929 and now they’ve changed all the codes in the Long Beach, you couldn’t build a house, your ground floor has to basically be uninhabitable space in Long Beach so a garage or something like that and if you’re going to build new construction. You know, before Sandy, we had about 4 instances where that apartment flooded just from rain because there were several rains on Long Island that were considered 100-year rain storms like where they would get 4-5 inches an hour, you know, crazy amounts of rain, and all of Long Beach flooded a couple of times just from the rain, you know, just from these summer thunderstorms."

"But you know I felt guilty, because you know when we talked about value and property value and things like that - I mean we had to sell the house because we’re middle class people and we would have lost all the money we put into it, but I think about those people and I wonder when the next thing’s gonna happen you know? They took out an FHA loan, they were first-time homebuyers, I think they put down 1% on the house, and you know I think, I just wonder about these policies, I wonder about all that kind of stuff, and I know that it’s easy for me to say now because I’ve extricated myself but I feel like I’ve learned a lot about the system and how there are so many things we have to start questioning."

"It was scary. They ended up having to retreat to the top floor of the house because the first two floors got flooded. The telephone pole went down in front so they couldn't escape out the front if they needed to. The next block over was one of the blocks that burned down... So they were just trapped in the house and just hoping that they would be ok. And then all my aunts and uncles - I have like 40 family members down there, and they are all in the Rockaways... a lot of [their homes] were just in bad shape. Only one of them ended up getting condemned, but the rest of them we're just in need of massive repair."

"Both sides of my family are from there. My mom is still in the house that I grew up in and that's the house that my dad grew up in. I spent my whole life out there until I moved out for college, and then I've been around Queens and stuff - but my whole family stayed down there."

"It was always a pain because [the] Rockaways have such a high water table, so any time it rained a ton... I remember when I was growing up it raining and it would be like get the wet dry vac and the sump pump because the water would be just coming through the floor. Not awful, just pick up all of the boxes and start draining it, but nothing terrible. Nobody expected that [Sandy] at all."

"That was one of the most devastating things for my mom, when she had to go down and clean out all of our childhood memories and stuff like that. All of our grammar school stuff and all of that stuff and then all of the pictures from when her and my dad were together. So she was helping for a little bit and looking around and then she's like, 'I just can't - just get rid of it and I'll be upstairs'. "

"My brother is in the Marine Corps, he was in Newport at the time, at the military academy, luckily. He's the only reason we had gas, because there was no gas anywhere around here and I was driving up and down everyday and we were out of gas. So he very dangerously filled up a U-Haul trailer full of gas canisters and came down and give it to everyone in the block. And he brought down a bunch of Marines, and they did a lot of work. They took time off they were excused out of classes and stuff."

"[At the] end of Howard Beach you start seeing water marks and stuff like that, like you can see the rail bridge from the beach in Howard Beach and Broad Channel so you could see [how] messed up it was. It wasn't completely taken out like the other rail bridge, but you could start seeing [the damage]. Then you get into Broad Channel and that's where you really started seeing the devastation. I mean, Broad Channel used to flood in a little bit of rain, everyone had to park their cars right in the middle because every street just flooded. It's completely even with the bay there so you start seeing that - one of the biggest things I saw was a boat in the second floor of a house - it was like sideways into it. That was my brother-in-law's best friend's house. Then you go over the bridge and you start to see some of it a little bit... it was all just covered in silt and sand but you could see where the bay and ocean met."

"Everything that happened with everybody's insurance, and the FEMA stuff and all that was - I don't think it could have been handled worse. It took them, let's see, eleven months to get the second floor rebuilt - I guess like the main floor. The basement we just gutted... it took longer because of the mold and all of that stuff. It was constantly treating this and doing that and then there's contractors that are taking advantage and all of that stuff and then the Red Cross was a joke... [they] showed up with like a bucket, a roll of Bounty, a couple of towels. It's like "Thanks, pal. Thanks for showing up." They were of no help."

"They [local government] weren't prepared... like not shoring any of that up, not properly having evacuation plans, and having completely incorrect flood zones. It was all off and they hadn't updated [it] for a very long time. And, I would say, the majority of the city agencies were neglectful... The sanitation department was really the only one that did anything. The police and fire were there, but they were a little overwhelmed and they were doing their job, but the sanitation department were really the ones who got Rockaway through it, and volunteers. It wasn't the city itself. It wasn't the Red Cross - they were complete failures."

"I lived in Greenpoint when Sandy struck. I lived... at the bottom of the hill and we threw a hurricane party that night... and we got really lucky because the street came up and then came back down and so where we lived... our street didn't flood, but a block away from our apartment it was flooded... we heard a loud bang and we saw a huge flash reflecting in the window. It was the power outage of New York, it was the explosion of the main power station. We saw this huge bright light like an insane light and then we didn't lose power but we noticed that tons of power was going out and our friends were calling us that were on the other side and they were like, 'it's crazy over here'."

"The next day I was just watching the news and since we're surfers - I wish people listened to surfers more when it came to the weather and storms, particularly what's happening with the beaches... Many surfers I knew where like, this is going to be really bad. We were all acutely aware of how bad it was going to be, just because of everything that was coming together for the storm: the timing that it was going to hit us, high tide there was a full moon, it was like every single thing that would have made the storm worse was happening -- and Surfers pay attention to that because it's going to be great waves, but we were also like, this is going to be devastating."

"We've lived in New York for 20 years. We have probably been going to Rockaway, I would say for 16 or 17 years. And when we used to go out there the beach was pretty deep compared to how it is now. it was like a pretty good size length of beach, and there would be nobody out there - nobody. It would be completely empty. All of [the] town houses they have built near the grocery store, that just started. They were constructing those things right when we started going out there, so it was all sand. There were none of those houses. It was the boardwalk and then sand... I grew up on the Jersey Shore... in Point Pleasant Beach, so I know the devastation that can occur, and a lot of my friends in Coney Island or on the Jersey Shore that I grew up with lost their houses, lost their businesses. So I knew the bigger impact that there was going to be for people. So I went out there 2 days later with a couple of girls, basically just to see how we could help."

"At the time, Occupy Wall Street had just ended so the Occupy movement started Occupy Sandy... I was superficially involved in Occupy Wall Street. I would go to marches occasionally. I wasn't living in Zuccotti Park. They really organized in a huge way in Brooklyn and in Manhattan and in Rockaway, but prior to them organizing it was just random people out there trying to help, and not everybody knew what the tools were that were needed but really quickly it became obvious that there were deficiencies in who was being helped and who wasn't being out. You know, when you go to Rockaway, after like 109th Street, it's nicer. The house get bigger, it's prettier, it's whiter. Those people had pretty much immediately Red Cross trailers. There is a really big Catholic school there that had set up a donation spot and people were coming in from everywhere. The gymnasium in that school was just full of clothes and products and that community had easy access. Their houses were destroyed there was sand everywhere. They were dumping everything out of their houses because it was all getting moldy, but if you walk below that, if you went into like 69th Street, there was nothing. There was nobody there to help. Some of those people live in high rises. They lost their electricity. They are low income. They don't have supplies. They weren't prepared, really. They lost their houses if they were in the smaller houses, and there was no government or even Occupy people there yet. It was just devastating. It kind of look like the end of the world over there; because if you did see people - they were like walking down the street with push carts trying to find anything that they could bring back to their home: food, water, batteries, whatever."

"Me and my friends made it a point to go. We would go either to the church what Occupy had organized in Brooklyn, and load our car up with supplies, or we would go to the church and the nicer neighborhood in Rockaway and load our car up with supplies, and then we would go down to the lower income community in the 60s. Early in the day we would just pop our trunk and just give people Pampers or whatever they need, then we would go into the high rises. They were like, 25 - 20 story buildings. We would fill our backpacks up and just climb up to the top and go knocking door-to-door, asking what do you need and with a notepad making notes of who needed what, and what apartment they were in. And then we would go back to the church in the nice neighborhood and get that stuff. Some people needed medical supplies. The Red Cross had medical supplies. They were not supporting this community. It took two weeks before I saw one Red Cross van down in that community."

"100-percent, they didn't have the financial capacity. It's expensive to be poor. To be honest, and I hate saying this, but we would have to leave that neighborhood by 3 p.m. Because at one point there was a shooting outside of the high rises that we were in. Just as we were coming down from inside the building, and keep in mind that you are in stairwells that are pitch black. We had our headlamps on but there were some people in there that would sketch you out and you weren't sure what was going on, and then to hear that there was a shooting that happened just outside - like am I putting myself in risk. what is going on? Simultaneously there were men that would come up, big guys that would come up to us with their eyes welled in tears looking for Pampers, and you're just like what the fuck."

Nicole looking at her partner's photo-book on Sandy and the Rockaways.

"Initially you're there to give people water and Pampers, and medical supplies and that kind of stuff. And then you're there too help clean out the house. And then you're there to help do construction. Then you're there to help pull out their walls. And so that was my process. By the time I left, I had started pulling out walls. There was a really big Thanksgiving celebration down there that a church and the Occupy Movement had organized for families that didn't have their electricity back on, because it took a long time to get electricity back. Everyone is talking about Puerto Rico not getting their electricity back, and I have connections to Puerto Rico too, so we talked about Puerto Rico as being 48 or 50 days out without electricity, which is fucked up beyond belief, but Rockaway - a lot of those people were without electricity for about a month."

Nicole looking at her partner's photo-book on Sandy and the Rockaways.

"People are not being educated and [as] storms get worse up the East Coast, and even in traditional hurricane areas we need to be educated. It needs to be part of the conversation. The conversation needs to be, a storm season is coming have these things don't wait until the last minute. As New Yorkers we are predisposed how to say 'fuck it, it will be fine the bodega will be open', and that doesn't always happen, so after that storm, I made it a point to help my community which was Rockaway. I felt like, sure these aren't my people, like I'm not friends with these people, but I use their community, I owe them something, I need to give back."

"So my parents are about a mile from the beach, and they are maybe about 3 miles south of the Verrazano Bridge, but kind of the Northeast portion of Staten Island... no one in our neighborhood [evacuated], everyone stayed. The only people were a couple down from us, they were in their 80s. They left but their son stayed in the house. They only left because their kids force them to, otherwise they would have stayed. My parents and everyone have been there for 40 years, [it] had never had a flood. The only flooding you get is some rain water from the sump pump, like everyone might get."

"My father and I were watching football, drinking wine; and my mom was watching Home and Garden in the kitchen. And we heard the sump pump go, but it wasn't raining, so we were wondering where the water is coming from. So we look outside and we see water almost to our top step, which is probably about three feet or so [of] water out in the street, and people walking down. Then we started taking things, and then we went downstairs and noticed that the water was coming through the windows; because it was above the windows. So we started taking important things out of the basement: the computer, some furniture - there was some furniture down there because my parents had just had the floors redone upstairs... Then one of the windows burst. We decided that we had to put the power out, because otherwise it could start a fire. So I did it because I'm much faster than my parents. So I went downstairs and in the amount of time it took for me to get to the end of the basement, all of the windows had then burst suddenly; so I put the power off, got a little bit of a shock and at that point the entire basement was almost filled with water. So I had to pull along the rafters, and then ultimately swim under boxes and furniture to get to the stairs, because everything had started floating."

"It's the footprint of the house, and it's not a short basement. It's a full floor 8ft it filled. And then upstairs, we didn't get any water coming in the doors, but there were some parts of the house where it came through the floorboards in low dips, so we moved some stuff from upstairs to the second floor even, but it was at that point already kind of looking like it was going to stop or it would recede. So then we just went all the way to the second floor and then my dad started cracking jokes about how we had wanted to have a pool in the backyard, so now we do."

Heather in her parent's basement, by the power breaker.

"I don't know who had it worse, me or them. Because they couldn't see me and they didn't know where I was, because at that point I had dropped the lantern and I knew where I needed to go. I had to get from A to B, and they are sitting there like, 'the basement is filled with water and we have no idea where Heather is'. My dad had my hand at one point but we couldn't move the furniture or the boxes."

Heather in her parent's basement, by the power breaker.

"[from the breaker to the door] it was 20ft. At the end it was right at the top, and I couldn't get air anymore so I yelled, 'I'm going under'. Because I knew I had to swim under, but they didn't hear me do that. He had my hand and I just let go and swam, so I don't know who had it worse. According to the electrician, because there was some water on the floor when I was walking, I said it's fine the power box is up high and I wouldn't have even been electrocuted."

"It would cause a short in the power box and then in some instances, that can start a fire. There were fires that started that way in various parts during storms and floods. So we knew that, and I'm just happy it's was me and not one of them."

"They had just redone the floors, so they had to rip up all of the hardwood flooring and all of the sub-flooring. The whole basement was gutted. What's crazy actually is the beautiful thing about Facebook; I had posted that my brother had got us a generator maybe 3 or 4 days later, and my friend Tommy who I went to elementary school with and have not seen in 20 years, asked if I wanted him to come and wire into our houses system. I said, 'that would be nice but my basements underwater. We can't do it.' And then he responds, 'I have two sump pumps, do you want me to come over and pump you out?'"

Heather, showing us how high the water was, and at what point she had to go back underwater to swim out.

"They had flood insurance because the house was still on a mortgage, at the time they were required by the bank to have flood insurance. So my next door neighbor who has owned his house outright for since 1960 something, he was the first owner. He didn't have any flood insurance, so it took a lot longer for stuff to happen for him. The storm hit in October and the house was done by February, perfectly done."

"By the time I got to the top of the stairs the water was all the way up the top. John grabbed her hand and it slid away and went into the water again."

"Around the corner here they lifted one house. On Greeley they have lifted three houses. Well they aren't attached. It's a little difficult to lift your house when you are attached to someone else. And now I have to get a certificate of elevation, because if I don't have that, every year my flood insurance could go up from 2-13%."

"When we moved here, we were not in a flood zone, but three years before the storm they redid the maps and they moved the flood zone to Highland Blvd. We still had a mortgage, so we had to get flood insurance. At the time, I was really annoyed. Now I'm glad they made us take it because anybody else who didn't have flood insurance, they were really stuck."

Anna Gaw: "They're supposed to be building, but I may be dead before it's done, the Army Corps of Engineers are going to be building a seawall all the way from here to Great Kills; which would make a big difference. A seawall, that would be really good."

"The only time we ever got water in the basement was with the sump pump. They had put storm sewers in Greeley and raised the levels over there. Before they did that, our next door neighbor never lived here and he said that the water had come up just a little to the top of the basement window, so maybe two inches outside. But once they put the storm sewers in in the early 70s, that stopped and then there was never any water [issues] again. [I] definitely [worry about flooding]. That’s why we were only half-heartedly trying to get [my son] to buy the house next door. I do worry about it. "

Hover your mouse over the image to see interview quotes and descriptions.

Meet our interviewees

Verna de la Mothe works at the Eugene Lang College at the New School for Liberal Arts. She was living in Hoboken, NJ when Sandy struck. She was on the third floor of her building when Sandy inundated her brownstone co-op. She watched as the water rushed in, and was stranded in Hoboken for two and a half weeks while the water slowly receded. One year later, she moved to Queens.

Elizabeth Murphy works in advertising and is a lifelong resident of Long Island, growing up on the water. Prior to Sandy, she never experienced any flooding event of that caliber in 30+ years of residing here. She has three boys, and was actually 37-weeks pregnant with her third son when Sandy struck. While her home is not on the water, it was still inundated by flooding, reaching 3-4 feet in her home.

Stephen Serwin works at the New School and had a home out in Long Beach when Sandy made landfall. He and his husband rented the downstairs unit and lived upstairs. When Sandy was still miles from making landfall, water rushed in and they helped their tenants escape to higher ground.Their tenants lost everything. Soon after, they rebuilt and sold the property.

Robert Kearns is an Analyst at NYU's School of Medicine. His entire family is from the Rockaways. When Sandy came, his parents home was devastated, along with the homes of most his family there. During the storm, he was in Queens and faced little direct damage from the storm, but after Sandy hit, he regularly went down to the Rockaways to help his family get supplies and fix damages.

Nicole Rodill is a trend forecaster and avid surfer who regularly surfs the waves off the Rockaways. After Sandy struck, Nicole and other fellow surfers decided to go out to the Rockaways and do what they could to aid the beach community they enjoyed so much. Nicole took supplies up large high-rises in the less-affluent areas of the Rockaways - making sure trapped families had vital supplies.

Heather Gaw is the daughter of Anna Gaw. They are both from Staten Island. When Sandy hit, Heather was riding out the storm with her parents in Staten Island. During the storm, she ran downstairs to shut off the power to prevent a fire. While at the breaker box, water rushed into the basement. Heather had to grasp at floor joists and swim out of the basement. Heather is a lawyer in the city, and her mother is retired.

explore the places affected

Hover your mouse over the image to see interview quotes and descriptions.

Hoboken is closer to Manhattan than a lot of areas considered a part of NYC. Here, you can see the whole skyline.

Hoboken saw severe flooding and damages to buildings, flooding 1700 homes and causing $100 million in local damages. Since Sandy, the NJ state government has made plans to build for coastal resiliency via their 'Resist, Delay, Shore, Discharge' program - intended to build up coastal defenses.

From the Interview | Verna de la Mothe:

[Regarding the city's preparedness for future Sandy-type storms] "As a matter of fact it may even be worse. Because the water damage from Sandy has left everything in such bad shape, I don't think you could really withstand another bad surge or water - heavy heavy heavy - like we had, the infrastructure is not going to hold because of the damage. I don't see anyone fixing it."

From the Interview | Verna de la Mothe:

"Finally we see the Army with their trucks picking up the elderly men and women, and I don't know where they were taking them maybe to a shelter somewhere... we were all still waiting for the water to go down. It took at least, I would have to say, from the time that I was there, it took at least two and a half weeks for the water to go down."

From the Interview | Verna de la Mothe:

"Thankfully people had a truck out there that had a generator for us to plug in our laptops and our telephones, so we could use that. And it was the only way that we could do that in the daytime. There were no lights in the street no lights anywhere. "

Sandy's storm surge soared right over this park and flooded into nearby homes and businesses.

From the Interview | Verna de la Mothe:

"That surge that was so high, it came over Sinatra Boulevard Park right over that and then went uphill and smashed downhill. That's when it pushed in the metal door to the basement, a thick metal door was broken in."

From the Interview | Verna de la Mothe

"I was still living in it while they were redoing the basement, and I couldn't take it anymore because I thought what they were doing was a patch job. I couldn't see them coming in where whole walls for gone and just putting in cement and patching things back - that's not going to hold. That's when I realized this is not good. So the first thing I did was make arrangements to move."

Nearly every street you walk down in Hoboken has new construction. Whether or not these works are in response to Sandy is unknown. But a bigger question is - are these projects taking into account what Sandy did and resiliency?

From the Interview | Verna de la Mothe:

"You know, everybody in the building that I was in - it was a small five story brownstone, it's a co-op, - and we all ran downstairs to see what was going on obviously. There was no lights we look downstairs at the steps to the basement. The water is coming all the way up to the first floor. We looked down in the street where you had like eight steps like a brownstone in the front - it was coming up all the way to the top. We couldn't even leave the building. The rain the water it just looked like there was no end that it was going to stop."

From the Interview | Verna de la Mothe:

"Each year it became worse and more devastating and it took longer for the water to go down [after storms]. And the cement and the concrete in the street was becoming soft and they had cave-ins. Cars were being leveled and it wouldn't hold up, and that's when I realized it was going to sink, sooner or later. So I made my plans to move out of there. I said, 'I can't take another year, I can't take another storm'. I just can't do this again."

Currently, Hoboken is seeing a revitalization of roads and store fronts.

From the Interview | Verna de la Mothe:

"The streets are contaminated - we were walking in them. It's freezing. The sewage is right there on the streets, you could tell where all wet and [what] had been damaged because there was ash - that's how bad it was there was like ash all over the place. It was one of the worst things I've ever experienced in my life. Without having, I mean just washing your face in your hands and having necessities of everyday living. It's bad, it was bad."

From the Interview | Verna de la Mothe:

"Finally in the park, the Red Cross came with their trucks and we're administering chili; because they said you need protein. Because everybody was, we all were shaking because we didn't have food. We had gone down to nothing. So they were giving us water and MREs to take back. The MREs were good because they also serve as a hot water bottle also because there is no heat. At that time it was turning into November, and it was freezing. It was terrible. The MREs did work to give us nourishment plus the warmth of the hot water so it was like we were in a battleground. Looking outside at night at the people walking the streets and trying to, I don't know what. I couldn't even tell you - you didn't even care you just knew that you were inside in the night in the dark, and in the day you were out exploring looking for a place to charge your cell phone and for food."

From this vantage point, you can see all the way down to the water, putting Hoboken's vulnerability into focus.

New Jersey's PATH train saw $300 million in damages from Sandy.

Hoboken Station was partially opened three months after Sandy. Fixing all the damages took months. Tunnels between NY and NJ are still being repaired today.

From the Interview | Verna de la Mothe

"The PATH train didn't come up until March or April and the New School supplied a bus that we met in a designated area to bring us to work."

Seaford was struck by the storm surge, like many other parts of southern Long Island. In the aftermath of Sandy, this small community came together to help each other rebuild.

From the Interview | Elizabeth Murphy:

"I cannot say enough about the Seaford School District. They worked so hard to get the kids back to normal... for the schools that didn't have power, they had them move entire classrooms to other schools with all of their desks and all of their stuff. They really were amazing. And they offered transportation to anyone who was displaced."

Before our interview started, Elizabeth drove me around her small neighborhood and pointed out this house to me, dubbing it the 'zombie house'. It was devastated by Sandy, and has now been left to sit, with black mold, snakes, or whatever else may be living inside it. She worries about her kids going near it.

From the Interview | Elizabeth Murphy:

[talking about her neighbor's damaged homes and their displacement] "I don't know how they secured the trailer, or whether it was covered, but they had one. That was a family of 7 living in a trailer and there was another family of five. For nine months, it was pretty brutal... And it was just weird, you know, the block was just pitch black for months because after the power was restored, they had to go individually to each house to have an electrician approve that the wiring was safe in terms of water damage and what not, which was great, but that took weeks."

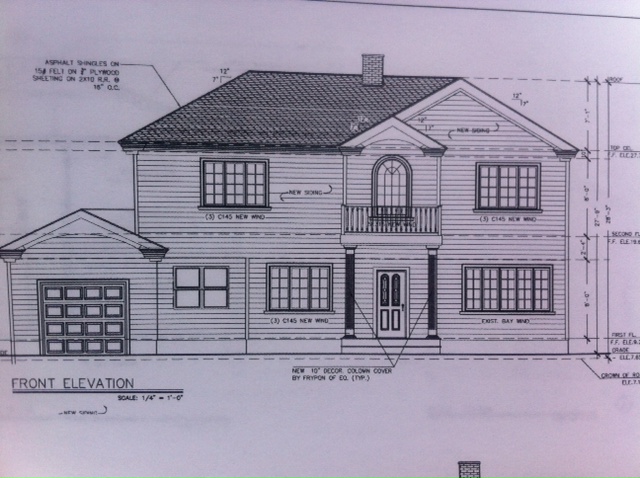

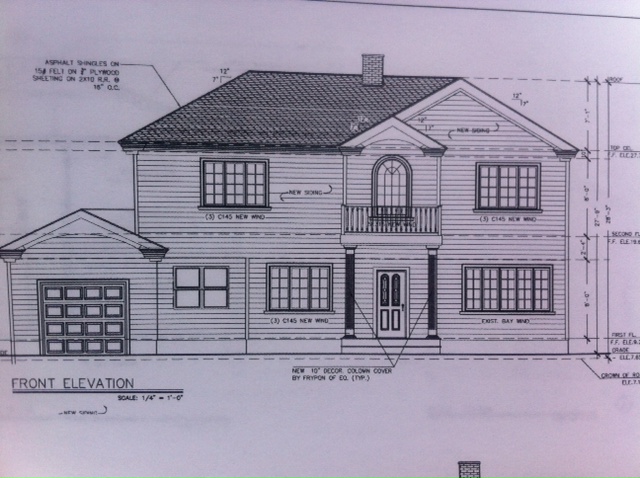

A Sandy house in Seaford being raised to prevent future inundation, and to be compliant with new FEMA flood insurance requirements, making some homeowners raise homes anywhere from 3 to 6 feet, depending. This home is right on the canal.

From the Interview | Elizabeth Murphy:

"We were told over the weekend that you should evacuate. I think it was recommended but not mandatory. And because I was pregnant I didn't really want to sleep on someone else's floor... we just didn't have a lot of places to go because so many people - I mean, everybody we knew was being effected."

Nearly everywhere in Seaford is a stone's throw away from the water. Elizabeth's home happens to be about 10 feet above sea level - but that didn't deter the devastating storm surge.

From the Interview | Elizabeth Murphy:

"Considering it was one floor, every wall was touched and what actually ended up being equally devastating was that the insulation pulled the water up, so we had 8 feet of mold around the perimeter of the house, so it was pretty bad."

Years after Sandy, you can still see some of the pitted canal walls beside homes now vacant, due to Sandy damage.

You can see the damage, but also just how high the water table is between tides.

From the Interview | Elizabeth Murphy:

"The reality is this is reality. I don't know what else I mean. I've read there's a lot about you know keeping storm surge from going, they seem to be very focused on Manhattan there are a lot of backwards and forwards around barrier beaches and things that are being done to try and protect our beaches. I believe that's a good place to focus. Because that's about the only way I think you can protect these towns that are really, frankly I mean Long Beach is the barrier island, but some of these exposed parts of the South Shore is our first line of defense. You know, the ocean front is only about 10 miles south of here so it is pretty intense, but I just unfortunately believe that like all other waterfront [areas] it will continue to become eroded and pushed back."

Within this small area, there are countless Sandy Houses being reconstructed.

From the Interview | Elizabeth Murphy:

"Once we were at least situated, at least in the rental house that we stayed in for about 6 months, and I went back to work after I had had the baby, and the kids are in school; it started to feel like, alright we don't live here but our life is somewhat back to normal. Financially, I feel like it will have impacts for many years to come because the years, especially when I think about the fact that we were paying mortgage and rent at the same time and taking on debt you know."

A short drive from Elizabeth's home is the marina. When walking around it, you can see how some of the boardwalk is in need of replacing. Between tides, the water table rose high enough to put into question if the marina should move inland several feet.

This spot definitely felt the brut of Sandy's storm surge.

From the Interview | Elizabeth Murphy:

"My advice to anyone who is in this area or any kind of area like this is just understand how well you're insured, and know where everything is, and get out of the house if someone tells you to leave."

After Sandy, Long Beach's beach and boardwalk were devastated, along with countless homes and businesses.

From the Interview | Stephen Serwin:

"Long Beach is an artificial island. It was made by a dredging operation in 1907. It was sort of marshland and it did have like a little - it’s more like [what] Fire Island is today with just a little spit of land, and there was a hotel there in the 19th century. And it was the first Long Island Rail Road line that went to the hotel."

You can see large boulders sitting on the beach, waiting to become a part of new jetties.

Way out on the jetties, you can see construction cranes doing the work to rebuild and fortify all of Long Beach. An effort to rebuild what was lost to Sandy and prevent future storm surges like that in the future.

From the Interview | Stephen Serwin:

"The trains weren’t running, your car was gone. No one’s cars survived, whether it was in a garage or not. So there was really no way out. And the National Guard came in right away. They were handing out those packets of food, you know [MREs]. People were living like that. So right away I could feel how we were different, you know the fact that we got rescued and we were taken to Tom’s parents' house and our tenants, you know, went somewhere else. I forget where they went, someone they knew had an empty apartment that was on a high floor so they went there. But you know, everybody was, everyone was basically shut out of habitable livings but they lived there anyway. And it was freezing, I don’t know if you remember, the week after there was a snow storm."

Jetties like this are constructed to protect the beach from breaking waves. They can help defend the beach from erosion and surges.

Cranes are easily spotted along Long Beach, they are either building jetties, rebuilding dunes, or doing construction on those beach front properties that line the beach.

From the Interview | Stephen Serwin:

"To get electricity back and get our house in order it took a month. So we were living with Tom’s parents for a month. You know, with with my dog, who was aged at that point and hard to walk and he was a very stressed out animal in the first place. I rescued him from the Brooklyn streets. At Long Beach we would do our daily walks, we were still walking through garbage and through sand banks and slicks of different chemicals, I have no idea what, you know but things that leach out of people’s houses. It was a really disturbing place to live after Hurricane Sandy."

Long Beach spent $40 million on its new boardwalk, opening it up in 2015. Other coastal resiliency efforts are still underway. The Army Corps of Engineers is spending $230 million to construct 8 jetties.

A common sight in Long Beach, an apartment building off the boardwalk is still in disarray, five years later.

From the Interview | Stephen Serwin:

"Flood insurance, the most I think people got was $80-120,000. For catastrophic damage... You show me a house in... on Long Island where $80-120,000 can make you rebuild your whole house, because that’s what it takes. And to jack it up and do all this stuff you need to do to bring it up to code."

You can see how the entire face of this building is still devastated, five years after Sandy.

New jetties and raised dunes are being put across Long Beach to protect against future storm impacts, but the construction can’t stop the volleyball players. Coastal defenses like this can play a big role in protecting inland communities from storm surges.

Five years later, you can still spot Sandy houses in Long Beach.

From the Interview | Stephen Serwin:

"It’s sort of like when you’re in a nightmare dream and you wake up and you’re, you think you’re okay but then you’re in another dream you know, where your dream has layers? We were walking around the neighborhood and when I realized how bad it was I was shocked. And you know we realized then that we couldn’t get out either, we had no cars, and there were sand banks everywhere adrift - the streets were full of sand dunes that had sort of been deposited by the water. 'Cause the water came up both sides of the island."

These bungalows are moments from Rockaway Beach. These properties all experienced flood damage from Sandy's 12ft storm surge.

You can see many bungalows still recovering post-Sandy, five years later.

From the Interview | Robert Kearns

"Once they finally got the boiler hooked up so they had heat, then they were staying there. Like we stayed there the first couple of nights because, though it happened a lot less than reported, there were some robberies and stuff like that. But our neighbor on one side is a police officer and on the other side is a fireman so they were around. They stuck around and made sure that once they could secure everything they came back."

The Rockaway Beach Boardwalk was destroyed by Sandy. The Boardwalk re-opened this year, thanks to $341 million spent by the city.

From the Interview | Nicole Rodill

"People didn't know how close the beach was until Sandy. Like we would be on the Subway with our surfboards and people would be, people from New York, would be like, 'where are you going? Where is there a beach?' People who have lived here their whole lives and they didn't know where the beach was. "

You can see across the beach new sand dunes and recently planted sea grasses - intended to defend the coast from future storm surges and inland flooding. Rockaway Beach lost 1.5 million cubic yards of sand, half the sand lost to all NYC beaches. The Army Corps of Engineers is spending $400 million to rehabilitate the beach here. They also plan to spend a further $3.6 billion to add levees, sea walls, and other coastal protections.

From the Interview | Nicole Rodill:

Interviewer: 'Do you think that the broader New York City area was prepared for the storm before it hit?'

Nicole: "Not at all. 100 [and] 20% not at all. Not even just the people. The government was not prepared. What happened in Staten Island really makes me mad like in an insane way, like almost as mad as I feel about what's going on in Puerto Rico right now."

From the Interview | Nicole Rodill:

"I'm not a weather person. I'm not an emergency management person. I'm not even a good surfer, but I know enough that if this is an island in the middle of this area that already has water currents that are coming through it that is built up - that is not a natural land mass. Make a fucking prediction about what is going to happen there. Come on, use a little bit of common sense, and nobody did. The people on the island were not prepared. The mayor of New York was not prepared. The governor of New York was not prepared. And I remember watching the news the day of Sandy thinking holy shit... people are going to die."

Everywhere, you can see new fortifications in the works, all intended to protect the coast from future inundation and storm surges.

When walking around the boardwalk at Rockaway Beach, it looks like you're stepping into a Van Gogh painting. It looks like a wheatfield, thanks to efforts to rebuild the dunes and reintroduce sand-loving grasses that can help fortify this beach community from future storms. The Rockaways lost 1.5 million cubic yards of sand from Hurricane Sandy, half the total sand lost to NYC's beaches.

Here, you can see new steps leading down to the beach that can be used for events. All a part of the rebuilding of the boardwalk.

You can see high-rises like this just steps from the boardwalk. Many living in these buildings were trapped for days without power.

From the Interview | Nicole Rodill:

"We have been going to Rockaway for 16 or 17 years, and when we used to go out there [it was] a pretty good size length of beach, and there would be nobody out there. All of [the] town houses they have built, that just started... it was all sand... It's expensive to be poor. To be honest, and I hate saying this, but we would have to leave that neighborhood by 3pm, because at one point there was a shooting outside of the high rises that we were in. Just as we were coming down from inside the building, and keep in mind that you are in stairwells that are pitch black. We had our headlamps on but there were some people in there that would sketch you out and you weren't sure what was going on, and then to hear that there was a shooting. Simultaneously there were men that would come up, big guys that would come up to us with their eyes welled in tears looking for Pampers, and you're just like, what the fuck."

Here on the roadside of the boardwalk, you can see how they've increased both the boardwalk and dunes by about ten feet.

A common sight in the Rockaways are these abandoned homes with roof or other damage. Walking past them, you can smell the mold from the roadside.

Some homes out in the Rockaways have signs from city programs aiding rehabilitation; many others have been left - abandoned and condemned.

From the Interview | Robert Kearns

"They [local government] weren't prepared... like not shoring any of that up, not properly having evacuation plans, and having completely incorrect flood zones. It was all off and they hadn't updated [it] for a very long time. And, I would say, the majority of the city agencies were neglectful... The sanitation department was really the only one that did anything. The police and fire were there, but they were a little overwhelmed and they were doing their job, but the sanitation department were really the ones who got Rockaway through it, and volunteers. It wasn't the city itself. It wasn't the Red Cross - they were complete failures."

From the Interview | Robert Kearns

"And the federal government too, was so far behind. FEMA was countering every claim and all this stuff. And I remember when I lived in Westchester, we had a terrible flood there in 2007. We lost the first floor of our house and it was so shortly after Katrina that FEMA just sent out money. We put in claims for like clothes and moving costs and they just cut me a check for like $1200. That's more than some people got for their house damage. They were reacting, trying to make it a PR thing and then this when it was a real emergency, some of the [FEMA] claims were paying out at like $800 to replace entire homes."

The Rockaways saw whole lines of track completely swept into the sea. After one-year of MTA repairs costing $200 million, the A-line was finally back up and running. This left many unable to go to work and behind on bills, long after Sandy.

From the Interview | Nicole Rodill:

"The fight that the mayor and the governor are having right now over NYC Subways right now is BS, just get it done. Guess what? Storms are going to keep coming and the Subway system is going to keep deteriorating; and so just get it done before the next storm happens... Initially you're there to give people water and Pampers, and medical supplies and that kind of stuff. And then you're there to help clean out the house. And then you're there to help do construction. Then you're there to help pull out their walls. And so that was my process. By the time I left, I had started pulling out walls."

From the Interview | Robert Kearns:

"[My family] didn't ever consider leaving. Like we talked about it a bit. It is kind of the way the world is going, the sea levels are definitely rising. The world is definitely getting warmer. Having grown up there their entire lives, they are kind of set on staying and saying "we are going to rebuild. It's going to be better than it was. We're going to keep going."

Just a short bus ride over the bridge from the Rockaways is neighboring Broad Channel. This community sits along a thin strip of land, and was severely damaged by Sandy.

A common site now are homes being raised and rehabilitated post-Sandy via the NYC Build It Back initiative. Currently, this program has helped over 10,000 homeowners rebuild their homes, and has raised 1,400 homes to meet new FEMA standards. Many of those homes can be spotted all over Broad Channel.

From the Interview | Robert Kearns

"[At the] end of Howard Beach you start seeing water marks and stuff like that, like you can see the rail bridge from the beach in Howard Beach and Broad Channel so you could see [how] messed up it was. It wasn't completely taken out like the other rail bridge, but you could start seeing [the damage]. Then you get into Broad Channel and that's where you really started seeing the devastation."

We saw countless homes still being rebuilt, raised, or completely empty lots where homes once stood.

From the Interview | Robert Kearns

"I mean, Broad Channel used to flood in a little bit of rain, everyone had to park their cars right in the middle because every street just flooded. It's completely even with the bay there so you start seeing that - one of the biggest things I saw was a boat in the second floor of a house - it was like sideways into it. That was my brother-in-law's best friend's house. Then you go over the bridge and you start to see some of it a little bit... it was all just covered in silt and sand but you could see where the bay and ocean met."

Meanwhile in neighboring Broad Channel, a common site now are homes being raised and rehabilitated post-Sandy via the NYC Build It Back initiative. Currently, this program has helped over 10,000 homeowners rebuild their homes, and has raised 1,400 homes to meet new FEMA standards. Many of those homes can be spotted all over Broad Channel.

Construction, everywhere. Here you can see a home being completely rebuilt and raised. You can see the water off in the distance, putting into view just how devastated this home was before Build It Back.

A frequent sight in Staten Island are the NYC Build It Back signs at construction sites. Build It Back only helps homeowners rebuild after all other types of disaster aid has been exhausted. Many homes are still left abandoned, or homeowners are left paying out of pocket for repairs.

From the Interview | Anna Gaw:

"When we moved here, we were not in a flood zone, but three years before the storm they redid the maps and they moved the flood zone to Highland Blvd. We still had a mortgage, so we had to get flood insurance. At the time, I was really annoyed. Now I'm glad they made us take it because anybody else who didn't have flood insurance, they were really stuck."

From the Interview | Heather Gaw:

"The only time I ever remember water in my lifetime was, I think it would have been Gloria. I might have been in the second or third grade at that time. Our house was fine but the one part of Highland Boulevard by us that always floods, even with a heavy rain. There were kids boogie boarding when the buses would drive by, but it was still not that high. I mean, you could walk. We were not anticipating it. We we're watching TV."

This house just by Cedar Grove Beach is being completely rebuilt without any living space on the ground floor. Many homes are being raised like this in NYC's coastal areas, now that FEMA has expanded their flood maps to include an additional 35,000 buildings, bringing the total to 67,000 at-risk properties.

From the Interview | Anna Gaw:

"Around the corner here they lifted one house. On Greeley they have lifted three houses. Well they aren't attached. It's a little difficult to lift your house when you are attached to someone else. And now I have to get a certificate of elevation, because if I don't have that, every year my flood insurance could go up from 2-13%."

This little beach has had serious dune restoration post Sandy. In the background, you can see how the entrance to the beach has a large dune with a protected walking path to use for getting to the beach.

Sand dunes and coastal rebuilding are everywhere in Staten Island. Unlike some of the other locations we went to, everywhere in Staten Island looks like the dunes and sea grasses have been there forever.

This entire beach was devastated by Sandy. Off in the distance, you can see the Verrazano Bridge, the road link from Staten Island to Brooklyn.

From the Interview | Heather Gaw:

"My parents are about a mile from the beach, and they are maybe about 3 miles south of the Verrazano Bridge, but kind of the Northeast portion of Staten Island... no one in our neighborhood [evacuated], everyone stayed. The only people were a couple down from us, they were in their 80s. They left but their son stayed in the house. They only left because their kids forced them to, otherwise they would have stayed. My parents and everyone have been there for 40 years, [it] had never had a flood. The only flooding you get is some rain water from the sump pump, like everyone might get."

From the Interview | Anna Gaw:

"They're supposed to be building, but I may be dead before it's done, the Army Corps of Engineers are going to be building a seawall all the way from here to Great Kills; which would make a big difference. A seawall, that would be really good."

This road was overtaken by Sandy's 12ft storm surge, flushing roads and homes with salt water.

From the Interview | Heather Gaw:

"It was right at the top and I couldn't get air anymore, so I yelled "I'm Going Under" because I knew I had to swim under. But they didn't hear me do that. He had my hand and I just let go and swam, so I don't know who had it worse. According to the electrician, because there was some water on the floor when I was walking, I said it's fine the power box is up high and I wouldn't have even been electrocuted. And he pointed out, but where are the outlets?"

Here you can see a parks and rec soccer field, adjacent to the new concrete FDR Boardwalk

This boardwalk has been entirely rebuilt. To the right, you can see tons of sand creating a wall between the boardwalk and the ocean. All part of new coastal defense works underway post-Sandy.

Today, Staten Island's beaches are lined with 10ft+ high sand dunes, covered in sea grasses. Efforts like these add serious resiliency to coastal areas, more than sea walls or other defenses. Plants with roots ground the sand and protect coastal areas from surges.

Heather Gaw, our interviewee, and Heather O'Brien, our Director of Events walk along FDR Boardwalk.

From the Interview | Heather Gaw:

"Maybe we expected a foot of water for a mile from the beach. We’re not oceanfront property. But in terms of the aftermath of the planning, some of the planned buyback programs that have been put forth I think are good, especially in the oceanfront properties. I don’t think we got… maybe we got a little bit of the attention nationally… we didn’t get Brad Pitt coming down to build a music village but we also didn’t have the damage that they had."

Walking along FDR Boardwalk from Midland Beach to South Beach, you can see how new coastal defenses are up. Dunes are 10-15 feet higher than they were before Sandy, and have lush sea grasses intended to fortify the coast from the next storm surge.

The entire coastline of Staten Island was inundated by flooding. Today, the state of New York is even buying people's properties to tear them down and let the land go back to nature - in the hopes of creating natural coastal buffer zones and defenses for future storm surges.

Since Sandy, Bowling Green Station has had major flooding fortifications put in - as part of MTA's 'Fix & Fortify' project. This station was completely flooded by Sandy's storm surge.

This whole area suffered flood damage due to Sandy's storm surge. Walking around today, it's almost as if nothing happened. Five years later, everything looks like it's back to normal - unlike many of the areas included here.

The NY Stock Exchange closed for two consecutive days after Sandy struck, the first time the NYSE closed due to weather since 1888.

Lower Manhattan is littered with historic monuments, like Federal Hall. These are some of the places that could be lost to future storms.

Wall Street used to have an actual 12 ft tall wall that was built by 17th Century Dutch settlers to keep Native Americans out.

Perhaps in the future, we'll be building walls like that to protect us from sea level rise.

This Subway Station was also devastated by Sandy. Like Bowling Green, it too is undergoing flood protection efforts via NYC's 'Fix & Fortify' program.

Peering through the never-ending construction, you can see yet another historic site at risk to sea level rise, Trinity Church.

One of our presidents, Alexander Hamilton, is buried here at Trinity Church. Yet another monument at risk to future floods and sea level rise.

Nearly every lower-Manhattan Station was struck by Sandy's surge, and saw severe flooding that left control panels unserviceable and left millions in the NYC-area unable to get to work. Wall Street Station is also having flood mitigation work done via Fix & Fortify.

Through Fix & Fortify, this station is having flood mitigation work done. During Sandy, this station was filled with water.

During Sandy, this tunnel was flooded with 100 million gallons of water, leaving severe damage in its wake.

Battery Park was a marsh after Sandy.

Sandy's surge aided by the higher than normal tide flooded the boardwalk and the surrounding area. Today, it looks like all that never happened.

Sandy left her mark on Pier A Harbor, causing $40 million in damages. It took three years for it to re-open.

Like the Battery, this entire coastal area was flooded by Sandy. Today, people are sunbathing and picnicking here.

This and countless other monuments and historic places are at risk to future storm surges, flooding, and sea level rise.

This lifeline for people in Staten Island was disrupted for only five days, but were still severely damaged by Sandy. $190 million was spent on two new ferries and flood defenses for both the Manhattan and the Staten Island sides of the ferry line.

The new South Ferry station had 15 million gallons of water flood into it, and only recently reopened after $340 million worth of post-Sandy repairs. Uniquely, the new South Ferry Station was only three years old when Sandy hit; thanks to $545 million in post 9/11 recovery funds.

Between the Staten Island Ferry and the Old South Ferry Station, you can see just how close the water comes up, at low tide - putting the magnitude of flooding seen here into sharp focus.

After Sandy shut down the Subway and closed Tunnels, people were relying on ferries. Weeks following Sandy, the NYC Department of Transit expanded ferry services.

Since Sandy, MTA is shoreing up all tunnels, including the LIRR tunnels at Atlantic Avenue Station through a network-wide $9.7 million system upgrade.

From here, you can see the NY & NJ Port Authority, a major artery of commerce for the NYC area. This infrastructure is also under threat. Sandy's surge reached 13-14 ft here, damaging 2,000 shipping containers, electrical systems, and other vital infrastructure.

The Red Hook neighborhood of Brooklyn is surrounded on three sides by water. When Sandy struck, it left debris and damaged buildings - even washing boats onto streets.

Walking along the waterfront, you can see the industrial past of Red Hook. Many of these buildings were inundated by Sandy's storm surge. All of Red Hook was within the mandatory evacuation zone for Sandy.

Walking towards Beard Street, which was like a river after Sandy, you can spot the occasional block of small bungalows. Properties like these were damaged by Sandy's surge.

Post home demolition, a lot being cleared in Red Hook post-Sandy.

From Conover Street, you can see the Statue of Liberty at sunset. This entire street was inundated with flooding, and also saw wind damage from Sandy.

$100 million is being spent on flood and coastal defenses for this one community.

Infamous now for both Houdini and Sandy. Aerial photos of Coney Island rides washed up into the beach are what most remember about Sandy. $48 million was spent to add sand and sand dunes to Coney Island's beach. $108 million was spent to repair and protect public housing in Coney Island that was damaged by Sandy.

There has been a lot of political back and forth on how best to repair Coney Island's boardwalk. Wood or concrete, that is the question. Currently, Coney Island's boardwalk has primarily had patch work done. Locals want to keep it wooden.

Like all of coastal NYC, Coney Island is vulnerable to sea level rise, storm surges, and flooding. Considering how badly Sandy damaged this community and all of NYC, one has to question if what is being done is enough.

The seven foot storm surge here devastated electrical systems and washed away amusements from the pier. Today the rides are all on the Boardwalk.

It cost $3.4 million in federal funds to repair the Steeplechase Pier - Coney Island's Pier.

After Sandy, it cost businesses a total of $5.5 million to fix amusements like the Cyclone and Wonder Wheel at Coney Island. Not to mention, the thousands of families displaced in Coney Island by Sandy.

Hover your mouse over the image to see interview quotes and descriptions.

Photos from our Interviewees

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Elizabeth Murphy

Photo by Stephen Serwin

Photo by Stephen Serwin

Photo by Stephen Serwin

Photo by Stephen Serwin

Photo by Stephen Serwin

Photo by Stephen Serwin

Photo by Stephen Serwin

Photo by Stephen Serwin

Photo by Stephen Serwin

Photo by Stephen Serwin

Damage in Astoria Queens, After Sandy

Photo by Mike McFarland

Photo by Mike McFarland

Photo by Mike McFarland

Photo by Mike McFarland

Photo by Mike McFarland

Photo by Mike McFarland

Our Interviewees, Elizabeth Murphy from Seaford, NY; and Stephen Serwin both gave us permissions to use these photos in our project. Here you can see the long road to recover, post Sandy. Also included here are some images from Queens, showing the stark difference in Sandy's impact from one area of NYC to the other.